My sister Bianka did something pretty sneaky recently. She pushed my curiosity button, and I was hooked immediately.

As you know from my last post, my doctor condemned me to a somewhat semi-invalid situation with nothing but restful inactivity which is not half as much fun as you might imagine. Even in the household of two retired fuddy-duddies with neither pets nor children, there are constantly small things that one “does”. Not doing them drives me bonkers but I must be sensible and continue to recline, if not gracefully, at least grateful that I do have the leisure to do so thanks to my husband who not only picks up the slack but cooks tastily.

However, physical inactivity leads to excessive browsing through social media, where I stumbled across my sister’s post of photos she took while walking through a Hamburg, Germany, neighborhood on a November weekend. The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg is a vibrant city with a long and proud past as an independently governed city-state.

Hamburg’s upwardly mobile history began in 808 CE, when Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor, and original Pater Europae ordered a “burg” or fortification to be built somewhere near the confluence of the rivers Elbe and Alster to better defend his Frankish realm against the raids of peoples not yet integrated into his domain, like Slavic and Saxon tribes. The castle became known as Hammaburg, eventually written as Hamburg. The meaning of the hamma part is hitherto unknown. Although such a riverside location close to the sea has enormous growth potential, it may invite calamity as well. The citizens of Hamburg have certainly experienced both.

Some aspects of the city’s past onto which my sister’s post touched became the starting point for a meshuggeneh internet search about Sephardim and Holsteiners. Such an odd combination, don’t you think? The photos Bianka posted contained place names like Krayenkamp, Markusplatz, jüdischer Friedhof [Jewish cemetery], and Großneumarkt which eventually lead me to the work of a Dr. Otto Adalbert Beneke (1812 – 1891) director emeritus of the State Archives in Hamburg and also a published author of historical non-fiction. Through Wikisource, I found his lovely and entertaining book called “HAMBURGISCHE GESCHICHTEN UND SAGEN, erzählt von Dr. Otto Beneke”, meaning “Stories and Legends from Hamburg, as told by Dr. Otto Beneke”. On page 280 we can read the story of a Marcus Meyer which I am retelling in English, below.

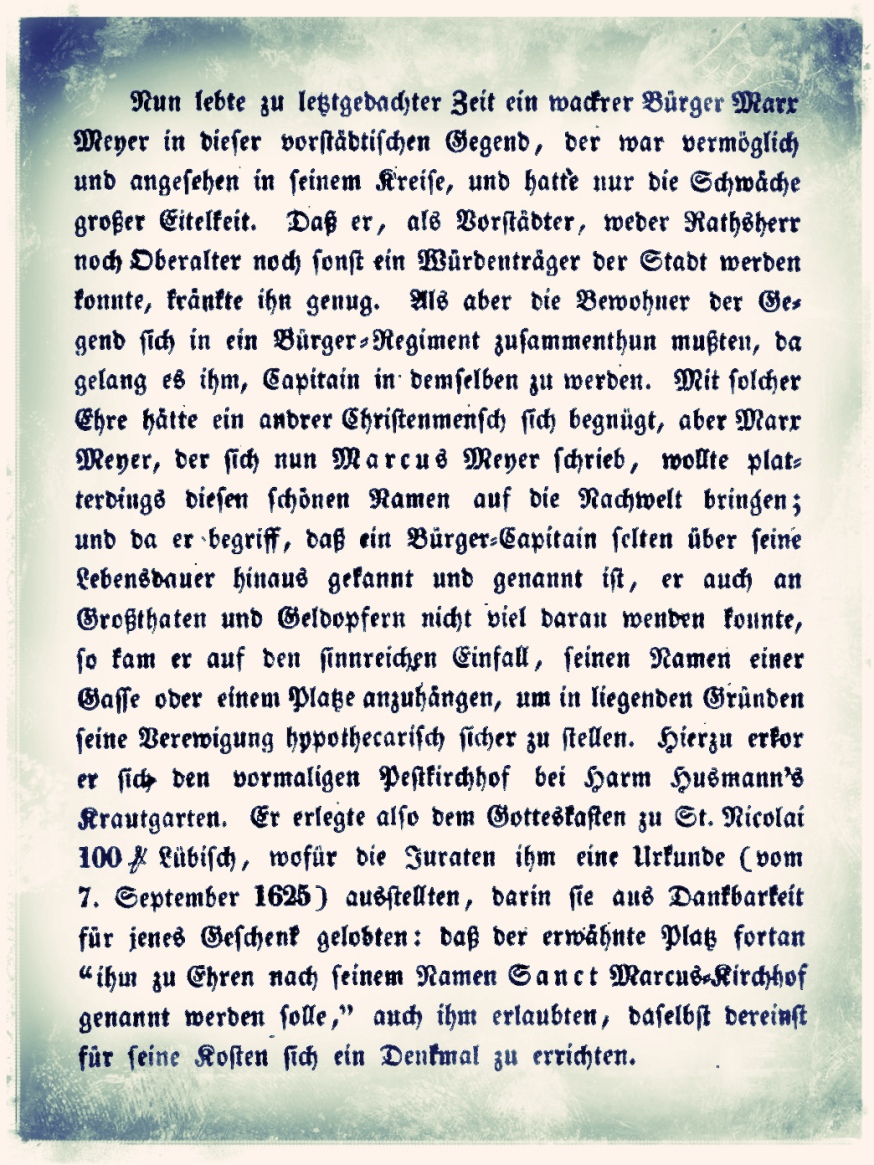

Dr. Beneke’s book is written in a manner of German used in the 19th century, printed in an antique blackletter typeface to match. It is a delight to read and I wish you could enjoy it with me. For German speakers: “… um in liegenden Gründen seine Verewigung hypothecarisch sicher zu stellen …”. This passage alone is as lovely as any Shakespearian sentence, expressive, precise, yet poetic. Sadly, it’s beyond my capabilities to write in an equivalent style in English, therefore I didn’t properly translate the narrative, choosing instead to retell it in my own words but following the storyline as closely as possible. In the “Marcus Meyer” Wikisource link above, the German text was transcribed into a modern font for easier comprehension. I do prefer to read the old script, though! I took a screenshot of a partial page to give you a glimpse of the original.

Excerpt, Otto Beneke “Hamburger Geschichten und Sagen”

My modern English version:

[Venice and Hamburg once shared a similarity, a place called St. Marcus Square. Both squares had winged lions. In Hamburg, the square no longer exists, but the lion image can still be seen in the Hamburg Museum.]

In the olden days, a neighborhood of Hamburg called Neustadt or New Town lay outside the gates and ramparts of the town proper or Old Town. Gradually, farmers from the surrounding countryside became inscribed in the St. Nicolai parish of Neustadt, populating the ever-growing area with their vegetable gardens which were called Kohlhöfe, cabbage farms. During the time of the 1563 black plague, the St. Nicolai church made two plots of land available to be used as burial grounds for the pestilence victims.

One of these was called the Krayenkamp because, according to legend, the corpses buried there lured large murders of crows [Kray possibly low German for Krähe = crow; Kamp = field]. Then again, “Kraye” may simply have been, ever so boringly, the name of a former tenant of that piece of land.

The other graveyard between the cabbage farms laid fallow till St. Nicolai leased it to a Harm Husmann in the year 1623. Farmer Husmann hoped to gain a nice profit from crops grown in the rich soil fertilized by all those ancestral bones. From 1627 to 1653, his plot neighbored yet another burial ground, that of the Portuguese Jews who had settled in Hamburg since about 1612.

There lived in Neustadt a man by the name of Marx Meyer, who lived a blameless life respected by his peers. His one weakness, though, was vanity. Oh, how he longed to be a proper dignitary in Old Town, a senator perhaps or an alderman, but such ranks were beyond the reach of a suburbanite. When permission was granted for the formation of a militia unit to safeguard Neustadt against roaming marauders, Marx Meyer soon advanced to the position of captain. Many a humble Christian would have been content with such a rank and the resulting elevated standing in the community. Not so our captain who realized that a militia rank would hardly inscribe his name in the history books, specifically his precious new name, since he now signed his name as “Marcus” Meyer. Captain Meyer’s determination to preserve this beautiful name for posterity was so strong that he came up with the ingenious idea of buying himself an alleyway or a square to be named after him. Why not mortgage his immortality to the chartered ground of Neustadt, he reasoned. He donated 100 Lübische Mark to the coffers of St. Nicolai for which the church treasurers awarded him with a name for the remaining acreage of the black plague boneyard next to farmer Husmann’s cabbage patch. In a document dated September 7, 1625, the churchmen pledged “that in his honor, the aforementioned square shall henceforth be known by his name as Sanct-Marcus-Kirchhof”. As a little bonus, they also allowed him to erect a monument to himself, at his own expense, naturally. Thus, in one fell swoop, a lowly Lutheran militia captain was not only inscribed in the temporal archives of Neustadt’s history but he became miraculously canonized for eternal immortality in the Papal register! Indubitably, Marcus Meyer died a happy man.

But already during his lifetime, Marcus Meyer’s so desperately craved name recognition slipped through the cracks of common remembrance in the local population. When a Paul Langermann built a house at said Sanct-Marcus-Kirchhof or St. Marcus Square in 1641, he attributed its name to the Evangelist St. Mark in whose honor he forthwith commissioned a bas-relief stone plaque picturing the saint’s emblem, a winged lion, to be incorporated in the front wall of his house.

Roughly one hundred years after these events, the Krayenkamp plot became the building site of the Hanseatic baroque Hauptkirche Sankt Michaelis, one of the five Lutheran main churches in Hamburg. The church is affectionately called “Michel” by seamen and citizens alike. Its copper-clad spire isn’t just a well-recognized landmark, it also functioned as landfall mark for ships sailing up the River Elbe.

The sentence in Dr. Beneke’s story in which I became most interested reads like this: “… Von 1627 bis 1653 haben dann dicht daneben die seit 1612 aufgenommenen Portugiesischen Juden ihre Todten bestattet.” Which translates to “between 1627 and 1653 the Portuguese Jews who had been accepted since 1612 interred their dead next door.”

Who were those “Portuguese Jews”, traders in the most part, who had indeed been tolerated and even appreciated in the Lutheran Hanse Town of Hamburg despite some intermittent ruckus with the clergy? I’ve come across references to Portuguese Jews before, including in historical fiction, but this time, I was determined to dig a little deeper. And, there arises quite naturally another question. Why were there such precise and limited dates given for their burial practices? Let’s begin with a little background research.

For the last couple of thousand years or so, circumstances drove many Israelites further and further away from Eretz Yisrael and their Semitic roots. The Babylonian and Egyptian exiles are known well enough, I assume, but according to a medieval Spanish text, there may also have been a Jewish presence in the Iberian peninsula as early as the time of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem which culminated in the destruction of the sacred Temple of Solomon in 587 BCE. Israelite captives were brought to Hispania by ship, the text states, and one such sea captain is even referenced by named as Phiros the Greek, who was commissioned by the Babylonian conquerors to transport the Jews. However, this has not been historically substantiated.

Significant waves of migrations were triggered by the Roman occupation of Judea leading to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple in 70 CE. During the Roman domination over the Levant and the Middle East, Jewish migrations as far as India and China are documented. Other groups began to spread through Central Europe and from there into the Slavic East, while a large number of Jews followed Phoenician trade routes and dispersed circum Mediterraneum, through northern Africa into the Iberian peninsula. Still, others wandered counterclockwise around the Mediterranean Sea through Greece and Illyria into Venice and Northern Italia – all the while settling along the way, forming new Jewish communities in the diaspora.

Historically, through these migrations, three distinct Jewish ethnicities developed out of the Biblical Israelite people. The Central European group became known as Ashkenazim [“Ashkenaz” meant Germanic in Medieval Hebrew], while the Mediterranean Jews of the Maghreb, Portugal, and Spain were grouped into the Sephardim [“Sefarad” meaning Hispania in Hebrew]. Lastly, in contrast to the developing European Jewry, the Mizrahim [“Mizrach” meaning East in Hebrew] are descendants of Jews who lived across the Middle East, in Babylon, Syria, Iraq, and far beyond, including the Caucasus regions and Yemen.

Taking a closer look at Jewish life in ancient Hispania, we see that it had its ups and downs, believe me! After the Roman empire pretty much fell apart with the influx of the Goth from the Baltic region across most of Europe, their western branch, the Visigoth, eventually settled in the Iberian peninsula during the 5th and 6th centuries CE. This worked out well for the Jewish communities therein until the formerly tolerant Goth converted to Catholicism toward the end of the 6th century, resulting in severe taxation and pogroms. Thus, when Tariq Ibn Ziyad rode into town in 711 CE, the establishment of a Caliphate was welcomed by Jewish leaders hoping for relief from oppression. The centuries of Islamic rule over the Iberian peninsula weren’t necessarily one long holiday on the sunny beaches of Andalucía for the Jews, but all in all, al-Ándalus constituted a period of relative peace for the roughly half a million Jews living in Spain at the time, making Medieval Sephardim the largest and most prosperous group of Jews in a diaspora.

Sephardic religious worship and its intertwined secular culture were shaped by the exchanges and discussions between Greek, Persian, Arabic, and Hebraic thinkers, philosophers, poets, mathematicians, and physicians during this invigorating period between late antiquity and the emerging Mediterranean medieval world. When Hebrew scholars began to incorporate Aristotelian worldviews into liturgical tradition, it marked the chasm between the Iberian Sephardic Rite and the worship practices of Ashkenazim which remained aligned with Rabbinic and Halakhic writings. Thus the Central and Eastern European Ashkenazim developed their distinct identity through introspection and stringent adherence to Hebraic traditions in a generally hostile Christian environment. Although they too benefited from periods of acceptance and respect, the Ashkenazim never experienced the same degree of an almost joyous mingling of cultures as the Sephardim enjoyed in the Iberian peninsula.

During long phases of relative freedom in Muslim Iberia, the Sephardim were not as severely segregated from their Christian and Islamic neighbors as happened later under Catholic rule, so they developed a language based on medieval Spanish mixed with Hebraic loanwords which is called Ladino. Just for the fun of it, I listened to a recording of a Ladino speaker and to my surprise, despite my poor Spanish, I got the gist of it [she spoke about the preparation of a plato típico, a regional dish which made it easier to comprehend 😎].

As we have seen, the expansion of the Roman Empire into Judaea and the destruction of the Second Temple triggered migrations not only to Iberia but also into Central Europe. Many of the descendants of Jewish slaves taken to Rome gradually drifted north across the Alpes, almost like a counter-migration to the Goth invasion of southern and western Europe. A Jewish presence in Köln [Cologne] goes as far back as 321 CE, and the granting of “Imperial Privileges” for the Synagogue of Cologne in the year 341 indicates a sizable community. These early settlers were soon joined by more and more displaced Jews, gradually making their way across Central Europe into areas we now call Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, Böhmen, Poland, Russia, and so forth.

Along the way, roughly between the 9th and 13th century, a new, uniquely Ashkenazi language developed called Yiddish. Its base is medieval High German, enriched with many Hebrew expressions. There are two main dialects, one more strongly grounded in German, while the other has its roots in Slavic and Romanic languages, and both are spiced with regional flavors. As a personal aside, I want to mention the first meeting between my German mother and my American mother-in-law. Neither spoke the other one’s language, but Yiddish made an initial conversation possible between these two lovely ladies. Subsequently, during my early married life in the US, every time my dear father-in-law used a Yiddish term, he would turn to me, ready to explain and I would have to laugh because it’s just German with a funky pronunciation! Like so many others, the following colloquial German expressions were derived from Yiddish: Bammel haben – anxiously anticipating something, like an exam; Ganove – crook; Mischpoke – originally extended family, later on, something more like rabble; Tacheles reden – clarifying something forcefully; Schmiere stehen – lookout [during the commission of a crime]; dufte – great, cool; Zoff – strife, troubles; geschlaucht sein – to be exhausted; Ramsch – cheap stuff; Blau machen – skip work or school without permission; ausgekocht – cunning; einseifen – to trick someone; Maloche – exhaustingly hard work; abzocken – to take advantage of or rip off someone [This is not a term a woman would use in polite company 😳]. From the 16th through the 20th centuries across Germany and Eastern Europe, Yiddish was much more than a language, it was more than a cultural assertion, it was the beating heart of a people, united in the midst of the diaspora. Despite the deep cleft between Ashkenazim and Sephardim, there is one thing at least their diasporic languages have in common. Traditionally both are written in a form of cursive Hebrew.

After our short linguistic digression, let us consider the fate of the Sephardim during the Reconquista, the “re-conquering” of the Iberian peninsula by Catholic rulers. The textbooks tell us that the Reconquista pitched Moorish invaders against the rightful rulers of the Iberian peninsula, Catholic Spaniards, who gloriously freed their realm from oppression. Especially during the years of Fascism in Spain, the Reconquista was termed as righteous Crusade versus Jihad. One might, however, view certain aspects of this nearly 800-year struggle a little differently.

Until the merge of the Kingdom of Castile with the Crown of Aragon, and the annexation of a part of Navarre, there was no “Spain” as we understand it in modern times. Conveniently skipping pre-history, we move straight into Iberian proto-history when the peninsula was populated by an assortment of indigenous tribes with the addition of a few Celtic immigrants. Beginning in the 10th century BCE, adventurous Phoenician traders, ever so courageously sailing along the Mediterranean seashore, settled in Hispania, establishing, among others a harbor now called Cádiz. Greek merchants followed suit, and ultimately the Carthaginians from North Africa populated large swatches of Hispania. With the final destruction of Carthage, Rome took over and gradually subdued all others until the peninsula became a Roman province during the rule of Emperor Augustus and beyond. It was Roman tyranny which brought large groups of Israelites to the Iberian peninsula in the first centuries of the Common Era.

And then came the Visigoth, see above.

When Maghrebine Berbers and their Umayyad overlords crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in the early 8th century, they intended to expand their sphere of influence into the Visigoth domain. A move, one would have to consider to be no different from previous ethnicities having crossed established borders in search of new territory.

It was, in fact, a very fortuitous moment for the fledgling Islamic caliphate to stretch its wings beyond the newly subdued North African region. The Visigoth kingdom in Hispania was mired in disarray through dynastic infighting. Thus, when Tariq Ibn Ziyad, possibly the son of a freed Libyan Berber in the service of Musa bin Nusayr, Governor of Ifriqiyah, the Maghreb as we call it now, fought the initial battle against the Visigoth king Roderic, it was no big surprise that he prevailed, at least in hindsight. Over the next few years, this initial victory snowballed into Umayyad rule across the entirety of the Visigoth’ Iberian holdings, with the notable exception of Asturia. Well, possibly. Historical records are a smidgen fuzzy about the details.

You see, there was this Gallaecian-Visigoth guy called Pelayu or Pelagius, son of Fafila Dux of Gallaecia. Dad having been killed by Wittiza, another one of a multitude of Visigoth kings drifting in and out of Iberian history during these times of upheaval, young Pelayu, our orphaned squire, became a latter-day hero of the Reconquista. Sometime between 718 to 740 CE, Pelayu allegedly rebelled against Umayyad rule. A small army under the leadership of a Muslim named Alkama and a Christian-Visigoth bishop named Oppa, who may have been a half-brother of murderous king Wittiza, was dispatched against Pelayu and his band of “30 wild donkeys”, as reported in Muslim chronicles. The donkeys won the day and victorious Pelayu returned to his ancestral region where the local leadership proclaimed him Principes of Asturia creating him the founding father of the Kingdom of Asturia, which for some time was pretty much the only Christian political entity in Islamic Iberia. Subsequently, many a Visigoth noble and disposed kinglet gathered in the Asturian exile planning revenge against the al-Ándalus subjugators. Skirmish by skirmish, Asturia grew into the Kingdom of Léon, out of which the Counties of Castile and Portugal arose. Eventually, and with a strong helping hand of other European ruling Houses, who worried greatly about the Islamic presence in Iberia, the Christian position in the peninsula strengthened and developed into several emerging powers, like Léon, Castile, Aragon/Naples, Pamplona/Navarre, Portugal, Barcelona/Catalonia, and so forth, gradually shrinking the Islamic power base to one last caliphate. Fast forwarding to 1491, the deciding victory of their Most Catholic Majesties of Castile and Aragon over the last Iberian Emir in Andalucian Granada, brought all non-Catholic culture in the Iberian peninsula to a crashing halt. The now dominant kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, incorporating also the southern portion of Navarre, would ultimately emerge as the unified Kingdom of Spain during the 16th century. Voilá, Catholic Spain was finally born, almost a hundred years after the rule of al-Ándalus in the Iberian peninsula had ended.

A few months after the victory in Granada, the infamous Alhambra Decree forced practicing Jews to leave the kingdoms of Castille and Aragon by midnight of July 31, 1492, or 8 Av 5252 in Jewish reckoning, the day before the Fast Day of Tisha B’Av, which is the annual commemoration of disasters that befell the Israelites through history during the month of Av. For instance, both Temple destructions happened in Av. During the summer of 1492, many Jewish families gathered their belongings and walked toward Lisbon and Porto in Portugal where they hoped for more tolerance when, only six years later, royal Portuguese ambitions threw another spanner in their hopes for a peaceful co-existence. The Portuguese king was eager to marry a Castilian Infanta but his chances were pretty much nil unless he could please her Most Catholic royal parents of his Christian zeal which lead to a forced mass conversion and related hardships. By 1497 most Jews had left the Iberian Peninsula in search of more hospitable shores, some of which were to be found eventually in northern Europe, mostly in Hamburg, Amsterdam, and London. Thus our “Portuguese Jews” of boneyard fame in Neustadt were the descendants of Sephardim escaping the Inquisition and the Edict of Expulsion of 1492 in Spain and subsequently the Portuguese Edict of Expulsion.

I wonder if anyone is aware that the modern Kingdom of Spain has acknowledged the ill deeds of the Houses of Castile and Aragon in the name of the Reconquista. Since the early 20th century, Spain has granted automatic citizenship to Sephardim returning to Spain. In 2012 Spanish citizenship was extended to the global Sephardic community without the requirement of residency. A truly unique gesture of reconciliation, as no other European nation has granted this privilege to atone for their past expulsion policies, of which there were many.

Now that we have returned in one piece from the hardships of Medieval Iberia, thus solving the “Sephardim” portion of the originally posed question of Sephardim and Holsteiners, we still have to tackle those Holsteiners, won’t we? The name goes back to the Holcetae, as the Romans called them, a Saxon tribe living along the northern bank of the River Elbe near Hammaburg. According to Medieval chronicler Adam of Bremen, their name translates to “those who dwell in the woods”.

Of course, Holstein can also refer to black and white milk cows, but as far as placenames go, our Holstein is the region to the North of Hamburg, traditionally occupying an area between the rivers Elbe and Eider. Throughout its history, Holstein was pulled hither and thither through frequent subdivisions, merges, and changes in ownership. At times belonging to the Holy Roman Empire, it was for far longer periods of time either a Danish possession or under the administration of the kings of Denmark. During the time of the Viking Age, when they sailed their sleek warships further and further South looting and burning, the Catholic Church moved inviolably North, converting Odin’s warriors to Christianity along the way. The Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen and Hamburg, jointly owned by the Holy Roman Emperor and the Catholic Church, had been given jurisdiction over The Faith in Scandinavia and the Baltic-North by the Pope. A certain Magister Adam, a member of the Church of Bremen, whose wisdom we’ve encountered just a few sentences ago, traveled with great enjoyment through Scandinavia. In 1070 he was a personal guest of King Sweyn II Estridssen of Denmark who told him long and detailed stories of Viking history over many a keg of mead, I imagine. Back home, Adam of Bremen spent three years writing his Œvre épique of the Archdiocese and her Bishops. His Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum [Heroic Tales of the Bishopric of Hamburg] wasn’t limited to church history, though, it included a Norse history with unique geographical details of Northern Europe based on his Scandinavian travels. And, remarkably, the Geste incorporated the story of the Viking’s transatlantic journeys to legendary Vinland in modern-day Canada, as the Danish King had told him. Magister Adam’s chronicles of Viking travel to North America were the first such reports outside of Norse Sagas.

As tantalizing as these Viking exploits are, we do have to focus on Holstein and, ultimately the town of Altona, because, as you well remember, we want to decode the reason why Jews buried their dead next door to the Hamburg St. Marcus square only for a few years which begs the answer to the simple question, where else did the Sephardim inter their dead? In order to approach an answer to this question, we have to take a look at something called the Thirty Years’ War. Extremely simply put, it was a Catholic versus Protestants [Lutheran Reformists] religious war that began in 1618. It turned into a major power play between twelve “Reformist” forces led by Sweden against six “Catholic” forces led by the Holy Roman Empire. When it was all over in 1648, thousands of castles and untold numbers of towns and villages were reduced to rubble, leaving large stretches of countryside scorched, mostly in the central combat region of what is now Germany. This war that began as a religious conflict, turned into a political war with profound results for the European balance of power and with a long-lasting effect on society at large. It claimed an estimated 20% of the European population, a geometric mean estimate of eight million people, of which less than half a million were combat casualties, while all others fell victim to famine and diseases like typhoid, dysentery, and the black plaque. Although this represents one of the highest war casualties ever recorded, I can’t help but think that nothing has changed through the intervening centuries. Civilians are still suffering the consequences of religious warfare and power games in contemporary conflicts.

Backpeddling ever so slightly, we return to Hamburg in the 16th century. Right next door to Neustadt, a fishing village grow along the banks of the River Elbe. It became known as Altona. And Altona became the first home of the German Jews when in 1611 Ernst Count of Schaumburg and Holstein-Pinneberg granted them the privilege of permanent residency. Soon thereafter Altona came under the jurisdiction of the king of Denmark who was also favorably inclined towards the Ashkenazim. Hamburg, on the other hand, wasn’t too keen on German Jews. They already had to deal with the Portuguese Jews, you see, and there’s a limit for tolerating those pesky Jewish migrants.

So there we have two communities in close proximity and a bunch of migrants clamoring for residency. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? As ever, back in the 16th and 17th centuries attitudes were, although black and white as in Christian versus Jew, nevertheless colored by practicality, politics, and Mammon. Sephardim in Hamburg were considered to be more valuable business partners owing to their Portuguese and Spanish connections which opened the spice, sugar, tobacco, cotton, and coffee markets to Hamburg traders. In general, the “Portuguese Jews” were wholesalers while the “German Jews” were retailers and as such small fry. The Jewish dilemma went back and forth between Altona and Hamburg for a while, during which time the Sephardim proudly presented many highly regarded members of their community, who were bankers, diplomats for foreign powers like Queen Christina of Sweden and the kings of Poland and of Portugal, there were also highly respected physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and thinkers, while the Ashkenazim were, officially, from 1567 onward only allowed residency in Hamburg as domestic employees in Sephardic households. Such irony, when you consider the many contributions to global knowledge by Ashkenazim. Beginning around 1627, the Hamburg Sephardim began a Talmud Torah, essentially a communal school to study Jewish Law. They met in the home of Elijah Aboab Cardoso for their lessons. In an amusing little aside, the aggrieved Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II lodged indignant objections with the Hamburg Senate concerning this “synagogue” because Catholics weren’t allowed to have a church in this Lutheran town, but nobody paid any attention to the emperor’s whining. The Hamburg Sephardim organized themselves into a proper congregation under the guidance of a Chief Rabbi in 1652. The Ashkenazim had to take a more roundabout approach through the Danish and Prussian holdings surrounding Hamburg. They established a congregation around 1671 in Altona. Against expectations, the Altona Ashkenazim proved to be an invaluable asset for the fledgling community at large. King Christian IV bestowed the privilege of ship-building to the Jews of Altona which was instrumental for the vast expansion of the whale fishing industry there, bringing prosperity to the whole town.

In addition to the separately weaning and waxing fortunes of the Ashkenazi and Sephardic communities in Hamburg, there were traditionally separate burying grounds for German and Portuguese Jews. The Hanse town of Hamburg did not grant burial permission to Jews, so Danish Altona hosted the first of the Jewish cemeteries that gradually appeared in communities outside to Hamburg. However, during the Thirty-Years’-War civilian life in the countryside became increasingly dangerous, hence the standing militia in Neustadt that appointed Captain Meyer, as we’ve seen above. The dangers in outlying areas through cruel and ruthless bands of mercenaries became so imminent that the St. Nicolai parish gave permission for Jews to be buried in a specially designated plot in Neustadt, for a hefty fine, of course. Five years after the Westphalian peace accord in 1648, the Altona congregations disinterred their dead and brought them back home. The Jewish cemetery of Altona is unique as it contains both Ashkenazi and Sephardic graves. In the Ashkenazi section, the gravestones are upright and have Hebrew inscriptions, while the Sephardic markers lay flat and show richly adorned Portuguese dedications.

It appears we have finally reached a conclusion to our search about Hamburg’s Portuguese Jews and the reasons for their temporary cemetery in Neustadt – not without uncovering a new puzzle, though: the curious fact that the Sephardic community in 1652 actively participated in the reburial of their ancestor’s remains, a practice which is not approved in Judaism. But do not fear, we will not go into it today!

Further Materials:

“The Thirty Years’ War: the first modern war?” a thought-provoking blog post by Dr. Pascal Daupin, Senior Policy Advisor at the ICRC, Policy and Humanitarian Diplomacy Division.

Mother Courage and her Children, the remarkable 1939 play by Bertolt Brecht. He uses the 30–Years-War to condemn the ideology of Totalitarianism and the actions of fascists.

http://jewishencyclopedia.com, this is the online version of an encyclopedia about all things Jewish published between 1901 – 1906 in 12 volumes. It has not been edited and therefore only contains references up to the 20th century.